Episode 49 – Slaves and Slavery in Texas Part 2 – After the Anglos Arrive

Slaves and Slavery in Texas Part 2 – After the Anglos Arrive

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

This is Episode 49 – Slaves and Slavery in Texas Part 2 – After the Anglos Arrive. I’m your host and guide Hank Wilson. And as always, brought to you by Ashby Navis and Tennyson Media Publishers, producers of a comprehensive catalog of audiobooks and high-quality games, productivity, and mental health apps. Visit AshbyNavis.com for more information.

In this episode I’m going to continue my discussion about a topic that often makes some folks a tad uncomfortable and that’s because I’m going to talk about slaves and slavery in Texas. In the last episode, I focused on slavery in what we call New Spain. That is the territories that were colonized by the Spanish in the 1500s up through the mid to early1800s. Slavery was a fact of life in the Spanish colonies, and then after Mexico declared their independence from Spain in 1810, and a rebel congress took control. In 1813 under the leadership of Father José María Morelos, they met at Chilpancingo they declared an end to slavery and to the casta or class system in New Spain. Now we have no records of whether or not the declaration of the Congress of Chilpancingo ever reached Texas.

Mexico achieved independence in 1821 and there were still about 3,000 slaves in the country and a several of those lived in Texas. In the summer of 1822, the new Mexican congress met and established a constitutional government for the nation. That congress quickly set out to promote the ideals of Chilpancingo and on September 17 issued a law abolishing racial categorization in official documents.

In a correspondence to the city council of San Antonio, Father Refugio de la Garza, a native Texan who represented the province in which he referred to the new social and political relations of the Spanish regime: “all that is over. We are all equal, and without this equality, our rights would not be inviolate and sacred.” After that date, Texas census reports drop all mention of casta data, showing that Mexico’s leaders accepted the new “race-free” society. However, slavery still existed and the fact that it did caused race relations to take a new and dangerous direction for Mexican and Spanish residents of Texas, with the arrival of the Anglo-American settlers in the course of the 1820s. For the most part, those early settlers had roots in the deep south and brought with them their prejudices and social customs. One of those customs was slavery.

While Mexicans generally objected to slavery, especially as it was allowed and implemented in the United State, many politicians turned a blind eye to the system. They were eager to profit from the production of cotton that Texans produced. Steven F. Austin, said, “The primary product that will elevate us from poverty is cotton and we cannot do this without the help of slaves.” As a result, Anglo-Americans where able to bring their family slaves with them to Texas. Until 1840, they were also allowed to buy and sell them. One concession the Anglos made was to agree that the Grandchildren of those original slaves would eventually be gradually freed upon reaching certain ages. When, in1827, the provincial government hinted it might emancipate slaves earlier, many of the immigrants made their slaves sign indenture contracts binding them for ninety-nine years. This was ostensibly to work off the purchase price, upkeep, and transportation to Texas of the slaves.

Mexican officials thought of this as the same as the tradition of debt peonage, and as a result Black slaves continued to arrive in Texas. As the 1820s came to a close, the most serious threat to Anglo slaveholders took place when on September 15th, 1829, Mexico President Vicente Ramón Guerrero, in commemoration of Mexican Independence, emancipated all slaves. The powerful friends that Austin had in Mexico’s government quickly secured an exemption from the law for Texas and slavery was permitted to continue in the province. The ability of Texans to continue to own slaves is considered by many historians to be a contributing factor in the eventual revolt of Texans for their independence.

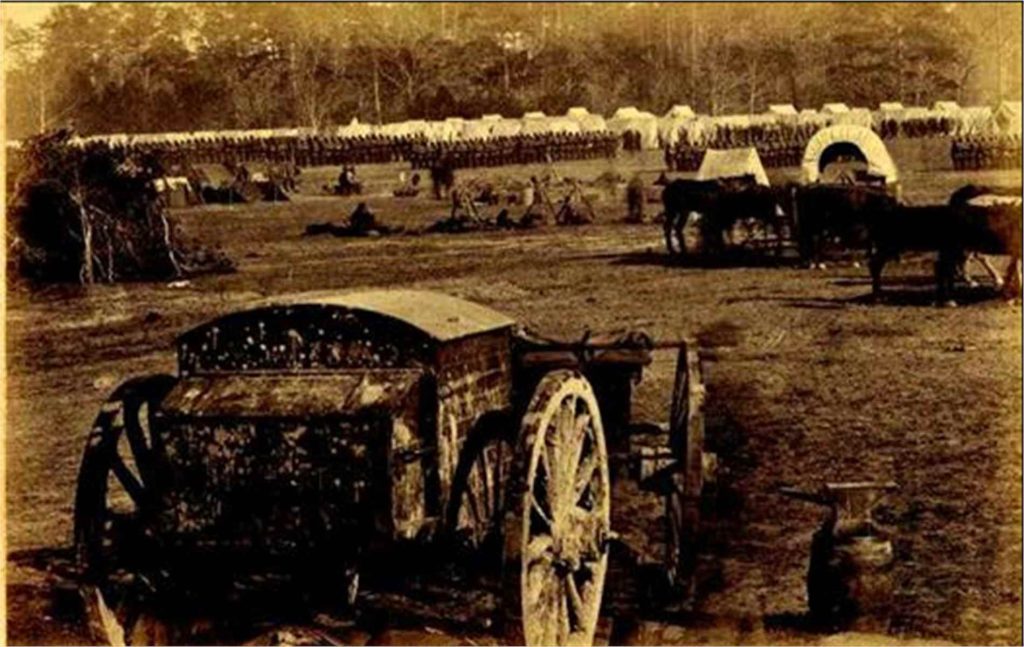

It’s important to understand that Texas was actually the last frontier of slavery in the United States. Between the years of 1821 and 1865, slavery spread over the eastern two-fifths of the state. While that might not seem particularly impressive, in reality it is an area almost as large as Alabama and Mississippi combined. The reality of slavery tightly tied Texas with the Old South. Regardless of this, in reality, a large percentage of the early slaveholders owned only a few slaves. Of course, as with everything, there were exceptions, one such was Jared Groce who arrived from Alabama in 1822 with ninety slaves. He immediately set up a cotton plantation on the Brazos River. He was the exception and the first census of Austin’s colony taken in 1825 showed out of a total population of about 1,800 people there were 443 slaves.

Over the intervening years, the Mexican government never adopted any effective policy that would have actually prevented slavery. Even though that was the reality, the threat of action made slaveholders nervous and some believe actually held back planters from the Old South from immigrating to Texas. By 1836 Texas had a total estimated population of 38,470 and about 5,000 were slaves.

It is acknowledged that the slavery issue and the disputes over it were not an immediate cause of the revolution. The fact that slavery was a part of Texas society was always in the background as what the noted Texas historian Eugene C. Barker called a “dull, organic ache.”

It was always there, in the back of people’s minds and was an underlying cause of the 1835-1836 struggle. More importantly, once the revolution was underway, many Texans became worried that the Mexican army and the Mexican government would order that their slave be freed. Failing in that, they would work to make sure the slaves revolted against their owners. One such event took place in the summer of 1835. Some Texas leaders, who were nervous about facing the forces of Antonio López de Santa Anna, declared that the Mexicans had actually tried to incite a slave rebellion. Rumors started that slaves who were on plantations on the Brazos river, “made an attempt to rise”. This was thought of as being a part of some elaborate scheme by the Mexicans and the slaves to seize the land.

Whites rounded up, whipped, and hung, and the fears of insurrection not only continued they grew as the military fortunes of the Texas army seemed to fall apart. Fear of marauding bands of slaves joining with Mexicans and Native tribes, fed into the fear that helped to spark the panic of the Runaway Scrape. Of course, the crisis passed with the Texans’ victory at San Jacinto, but gangs of runaway slaves did take part in a guerrilla-like warfare for the remainder of the 1830s. As a result of these types of issues, once independence was declared and a constitution was adopted, according to a Texas Supreme Court Justice they made certain to , to “remove all doubt and uneasiness among the citizens of Texas in regard to the tenure by which they held dominion over their slaves.” Section 9 of Constitution of the Republic of Texas read in part as follows: All persons of color who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas, and who are now held in bondage, shall remain in the like state of servitude… Congress shall pass no laws to prohibit emigrants from bringing their slaves into the republic with them, and holding them by the same tenure by which such slaves were held in the United States; nor shall congress have the power to emancipate slaves; nor shall any slave holder be allowed to emancipate his or her slave without the consent of congress, unless he or she shall send his or her slave or slaves without the limits of the republic.

After Texas gained independence, slavery expanded rapidly. By the time Texas was admitted to the union in 1845, there were at least 30,000 enslaved people in Texas. After Texas became a state, that number skyrocketed, The 1850 census reported 58,161 slaves, which accounted for over 27 percent of the 212,592 people in Texas. The 1860 census shows an even greater increase with a population of 182,566 slaves, over 30 percent of the total population. In reality, slaves were increasing faster than the population as a whole.

So yes, Texas was indeed a slave state and a very active one at that.

That’s going to do it for today. Next episode I’ll continue my look at slaves and slavery in Texas. I’ll take a look at some of the other slave insurrections in Texas and the growth of slavery after Texas became a state until it seceded from the union.

Please subscribe to the podcast, I’m back and I’ll keep posting new episodes, sometimes though life gets in the way which is why there’s been a gap between episodes. If you want more information on Texas History, visit the website of the Texas State Historical Association. I also have four audiobooks on the Hidden History of Texas, The Spanish Bump Into Texas 1530s to 1820s, Here Come The Anglos 1820s to 1830s, Years of Revolution 1830 to 1836. And, my latest A Failing Republic Becomes a State 1836-1850. You can find the books pretty much wherever you download or listen to audiobooks. Just do a search for the Hidden History of Texas by Hank Wilson and they’ll pop right up. Or visit my website https://arctx.org. By the way if you like audiobooks, visit my publisher’s website there’s an incredible selection of audiobooks there. In addition to mine you’ll find the classics, horror, science fiction, mental-health, and much more. Check it out visit https://ashbynavis.com

Thanks for listening y’all