The Battle of Glorieta

Episode 60 – –The Civil War and Texas – The Battle of Glorieta

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

I’m your host and guide Hank Wilson and as always, the broadcast is brought to you by Ashby Navis and Tennyson Media Publishers, Visit AshbyNavis.com for more information.

We are smack dab in the middle of telling about the history of Texas during the Civil war. There’s no exact count of how many battles and skirmishes that were fought in Texas. In fact, most of the Texans who fought for either the confederacy or the union took part in battles in Tennessee, Virginia, or elsewhere in the South. There were however four notable battles that did take place in Texas, well the first actually was in New Mexico, but it started in Texas. They are on March 28, 1862, Battle of Glorieta, the Battle of Galveston October 4, 1862. the battle of Sabine Pass, on September 8, 1863, The Battle of Palmito Ranch, was the last battle of the civil war on May 13, 1865.

What I want to talk about today is one of what many historians consider to be a key (while not necessarily a major battle) is known as the Battle of Glorieta, which occurred on March 28th, 1862. Now it actually took place, not in Texas, but in New Mexico at Glorieta Pass which is in Far West New Mexico.

The Confederate force, named Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley’s Army of New Mexico, actually consisted primarily of men from Texas. The “army” invaded New Mexico, which was Union Territory and captured Fort Fillmore which was located close to the settlement of Mesilla. The “army” then won another skirmish at Valverde in February of 1862. After that they moved northwest, moving along the banks of the Rio Grande, and by early March they occupied Albuquerque and Santa Fe. After their successful mini invasion, they stopped to gather supplies and rest while they planned their attack on Fort Union which was the Federal Supply Center. It was about 100 miles northwest of Santa Fe and was a major stop for travelers who were on their way to the gold fields in Colorado.

Meanwhile, Colorado attorney Colonel John Slough put together a group of volunteers from the gold fields and joined together with detachments of cavalry and infantry from Fort Union to create a force of about 1,300 men. Then on March 22nd, Slough led the group on a march to engage the Texans near Santa Fe.

Simultaneously, Sibley moved his main column of men towards Fort Union. Meanwhile, a confederate force of men led by Major Charles Pyron who stayed in Santa Fe, decided to move towards the east along the Santa Fe trail.in an attempt to find and engage with the union forces.

He led his troops from Cañoncito in the early morning hours of the 26th of March and almost immediately ran into Slough’s advance guard. Slough guard had just about 420 men and was led by Maj. John M. Chivington. The two forces see each other, the Texans decide to form a traditional straight ahead battle line that blocked passage. The Union forces simply outflanked them by climbing up the hills that bordered the trail. Seeing they were about to lose, the confederate forces retreated back towards a small valley that is known as Apache Canyon. This valley had multiple fields that had been cultivated for farming and it was there they decided to setup another similar battle line, much like the one they had abandoned.

Once again Chivington simply ran a flanking action and this time, since it was more open, he also had his cavalry charge the Texans. As a result, at least 70 Confederates were captured, it is estimated that 4 others were killed, and about 20 were wounded. After this setback, Pyron retreated back to his main camp at Cañoncito from where he dispatched a messenger asking the main Texan force to send him reinforcements. Meanwhile Major Chivington, who also suffered some casualties, 5 men killed and 14 wounded, decided to return to the main Union camp which was 12 miles away at a station known as Koslowski’s Ranch.

A couple of days later, on the morning of March 29th, Lt. Col. William R. Scurry, led a confederate force eastward. This action left the primary supply train at Cañoncito almost unguarded. Those who remained consisted of a handful of noncombatants who were armed with a single cannon. They were horribly outmanned and outgunned for any type of encounter.

The battle of Glorieta started with a few scattered shots around 11 am. The Texas force of 1,200 men engaged Colonel Slough’s 850-man force who were resting at Pigeon’s Ranch, another of the stops on the Santa Fe Trail which was actually about a mile east of Glorieta Pass. Meanwhile the remainder of Slough’s Union troops which were led by Major Chivington, had already moved to attack the Texas forces who remained at Cañoncito. Chivington was aggressive and pushed his men through a heavily wooded mesa (a flat piece of land that looks like a table) which was south of the trail. That is where the two main forces engaged near Glorieta. Like most skirmishes that took place during the civil war, the two sides fired at each other from their positions on each side of the Santa Fe Trail. Finaly in mid-afternoon, Confederate force leader Scurry had his men outflank the Union line, which forced Slough to withdraw. He then created a 2nd defensive line near Pigeon’s Ranch. Well, this forced the union forces to surrender the high ground to the Texans which, in turn, forced Slough to try and establish a 3rd position a half mile further to the east. Needless to say, the Confederates followed, and the two sides began throwing half-hearted cannon and small-arms fire at teach other. Slough finally withdrew his forces back to Koslowski’s Ranch, which gave Scurry sole possession of the field.

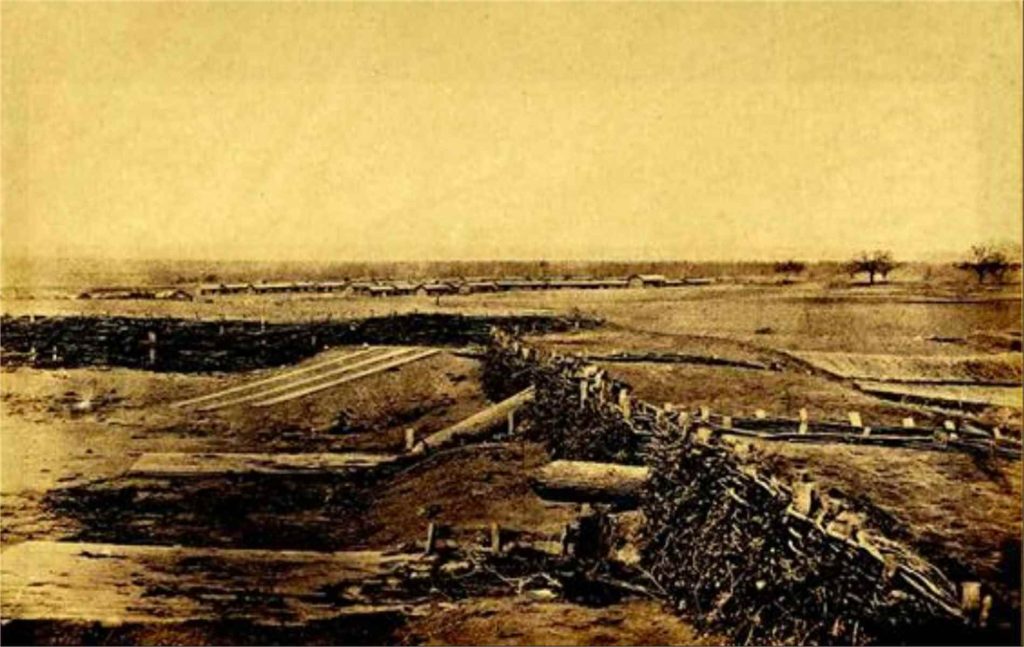

While the battle around Pigeon’s Ranch continued, Major Chivington’s party had taken up positions some 200 feet almost directly above the camp where the Texans had left their wagons at Cañoncito. They easily descended the slopes quickly disabled the one cannon that had been left and then burned every one of the 80 wagons of the supply train. Of course, this destroyed Scurry’s reserve ammunition, baggage, food, forage, and medicines. After destroying the Texans supplies, they federal forces simply retraced their route and joined up again with the main force at Koslowski’s Ranch. The action at Cañoncito effectively decided the fate of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico.

Fighting did continue until darkness fell and at the end of the day the Texans suffered 48 killed and 60 were wounded. The Union forces had suffered almost the exact same number of casualties. Slough’s men returned to Fort Union and Scurry stayed at Pigeon’s Ranch another day so he could have his wounded treated and bury his dead. The dead were placed in a mass grave along the Santa Fe Trail near the hospital. As was the case in many such battles both sides claimed victory, but the reality is what the Union forces did to the confederate supply camp at Cañoncito forced Sibley to withdraw from New Mexico and halted any Confederate advance into the Far West. That’s going to do it for this episode. Next time I’ll talk a look at the battle of Galveston and the battle of Sabine Pass. If you get a chance, please subscribe to the podcast. If you want more information on Texas History, visit the website of the Texas State Historical Association. I also have four audiobooks on the Hidden History of Texas, The Spanish Bump Into Texas 1530s to 1820s, Here Come The Anglos 1820s to 1830s, Years of Revolution 1830 to 1836. And A Failing Republic Becomes a State 1836-1850. You can find the books pretty much wherever you download or listen to audiobooks. Just do a search for the Hidden History of Texas by Hank Wilson and they’ll pop right up. Or visit my website https://arctx.org.