1900 Galveston Hurricane

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

1900 – The Galveston Hurricane

The city of Galveston sits on Galveston Island which is two miles offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. The island is only about 50 miles from Houston, and it is a part of what are called the barrier islands. The islands sit between the mainland of Texas and the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. As such, they often bear the brunt of any storm that arises in the Gulf. Galveston has a natural harbor and in the early days of Texas was regarded as the best Gulf port site between New Orleans and Veracruz.

Karankawa Indians lived on the island and it is thought to be the most likely location of the shipwreck landing of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in 1528. It received its name in 1785 from José de Evia, who named it in Bernardo de Gálvez, the viceroy of Mexico. Mapmakers then used the name Galveston for the entire island and in 1816 Louis Aury established a naval base at the harbor in order to provide support for the Mexican revolution.

It was during that time when the pirate Jean Laffite, set up a pirate camp called Campeachy to dispose of contraband and provide supplies for the freebooters. In 1821, however, the United States forced Laffite to evacuate. Mexico designated Galveston a port of entry in 1825 and established a small customshouse in 1830. During the Texas Revolution the harbor served as the port for the Texas Navy and the last point of retreat of the Texas government. Following the war Michel B. Menard and a group of investors obtained ownership of 4,605 acres at the harbor to found a town. After platting the land in gridiron fashion and adopting the name Galveston, Menard and his associates began selling town lots on April 20, 1838. The following year the Texas legislature granted incorporation to the city of Galveston with the power to elect town officers. Between that time period and 1900 Galveston struggled during the civil war and then in 1867 the island and town was ravaged by the yellow fever, and it is estimated that 20 people a day died from the disease. Regardless of the hardships, Galveston eventually thrived and in fact, It had the first structure to use electric lighting, the Galveston Pavilion; the first telephone; and the first baseball game in the state. The Galveston News, founded in 1842, is the state’s oldest continuing daily newspaper.

Back in the old days, many of us would get up early in the morning, walk out to our front porch and pick up the daily newspaper. It was a ritual, that was how we got our news. Now we don’t do that anymore, most of us turn on our TVs, phones or computers and get our news from there. But back in 1900, on September the 8th, if you were one of the approximately 38,000 people who lived in Galveston, Texas at that time and had awakened early and picked up your morning edition of Galveston News, you would have seen a story, not a headline, but a story on page 3 about a tropical storm that seemed to be roaming about in the Gulf of Mexico. That’s not an unusual type of story for people living along the gulf coast, especially during the month of September.

However, one thing that made this story a little different was that on Friday, The Weather Bureau, now days known as the National Weather Service, had placed Galveston under a storm warning. The paper also contained a small one column story, that said that great damage had been reported from communities on the Mississippi and Louisiana Coast from the storm. Unfortunately, the story, which had originated in New Orleans at 12:45 AM, was only one paragraph and didn’t really contain much information.

The local paper did print a story beneath the report that said, “At midnight the moon was shining brightly, and the sky was not as threatening as earlier in the night. The weather bureau had no late advice as to the storm’s movements and it may be that the tropical disturbance has changed its course or spent its force before reaching Texas.” So based on that type of reporting, citizens were not really prepared for what was to occur.

People in Galveston had been made aware of the storm once it was reported as being over Cuba on September 4th. Remember, though, this was 1900 so communications were sketchy at best and those ships who were in the gulf had no way sending weather observations to shore stations. No satellites existed there was simply no way to warn people what was coming.

This particular Saturday started out much like every other weekday. Now I say weekday because in 1900 a six-day workweek was common. There was more rain and wind then usual, but nothing that would have aroused too much suspicion. Eventually though people began to notice the tide began to run higher than usual, but may Galvestonians were used to what they called “overflows” which occurred when high water crept over the beachfront. In fact, most houses and stores were elevated because of that type of issue.

This time was different, because the tide kept rising and moving further inland and the wind showed a steady increase. Isaac M. Cline, who was the Weather Bureau official in charge locally, actually went around town in his horse-drawn cart and warned those people living in low areas to evacuate. However, as people are often stubborn, few took his warnings seriously.

Soon the bridges that connected Galveston Island to the mainland collapsed, and those people who lived along the beach had waited too long and were unable to even seek shelter in some of the larger building in the downtown area.

As you would expect, the houses closest to the beach fell prey to the storm first. In fact, the storm moved debris from one row of buildings and sent it smashing against the row behind it until almost two-thirds of Galveston was destroyed. Any person who was outside and trying to make it to higher ground were often hit by bricks and lumber from destroyed buildings.

By 5:15 in the afternoon, the wind was record at a consistent eighty-four miles per hour, over a five-minute period. Gusts of 100 miles per hour were also recorded and some later estimates believe gust reached more than 120 miles per hour. The wind wasn’t the worse of the storm, just about 6:30 in the evening, a wave came sweeping across the shore causing a rise of over four feet in depth which put the entire city at least 15 feet underwater. This wave cause the majority of the damage the city endured. By 10:00 PM, the tide began to fall and the worse was clearly over.

Sunday September 9th dawned, and the destruction and devastation was clear to all of the survivors. The city was completely in shambles. In the city alone, somewhere between 6 and 8 thousand people had perished. Over the entire island it’s estimated that between 10 and 12 thousand people lost their lives.

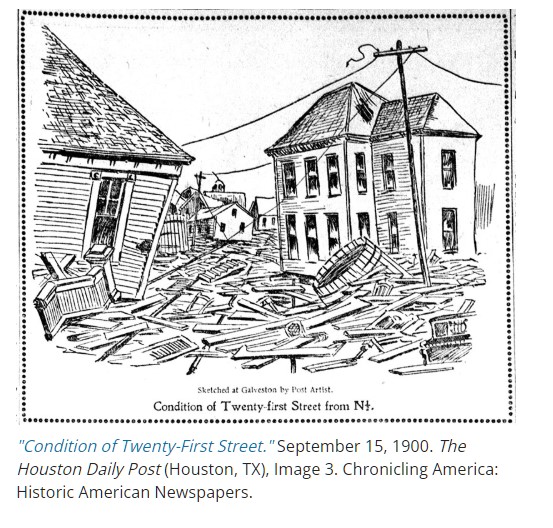

Newspapers from around the nation reported on the disaster. The September 10th edition of the Salt Lake Herald had the headline, “Pestilence Menaces Stricken Galveston” with the secondary headline of “Decaying bodies everywhere fill the air with odors and Sickness is on the increase”. The San Francisco Call “Thousands of Dead Strew the Ruins of Galveston.” In the Houston Post on September 15, there was a drawing labeled, “Condition of Twenty-First Street” the drawing showed the rubble of homes, giving a clear depiction of the devastation the city endured.

Due to the high death toll, the Galveston storm that year was, up until the 1980s, still regarded as the worst recorded natural disaster ever to strike North America. In response to the destruction, the city built a six-mile-long seawall that stands at least 17 feet above the average low tide, and that protective barrier has been extended since then. The city learned its lesson from the storm and is now constantly on watch for this type of storm and is constantly revising and trying to strengthen its defenses against the power of hurricanes. In the next episode, I will talk about some of the most powerful storms to hit the Texas coast during the 1960s and 1970s.